Cover

Cover

Frontispiece

A GLIMPSE OF THE

HEART OF CHINA

by

EDWARD C. PERKINS, M.D.

ILLUSTRATED

New York Chicago Toronto

Fleming H. Revell Company

London and Edinburgh

Copyright, 1911, by

FLEMING H. REVELL COMPANY

New York: 158 Fifth Avenue

Chicago: 123 North Wabash Ave.

Toronto: 25 Richmond Street, W.

London: 21 Paternoster Square

Edinburgh: 100 Princes Street

This little sketch began as a letter, but grew very naturally into something of a more general character because of its subject matter. It is hoped that it will be of interest not alone because of the capable, devoted and self-sacrificing woman of whom it gives an inadequate picture, but also because it would pass on a vision of the love of the Master.

E. C. P.

St. Luke's Hospital,

New York City, April 4, 1911.

I wish to acknowledge my indebtedness to the Christian Herald, through whose courtesy I am using the picture of Dr. Stone that serves as the frontispiece.

E. C. P.

TO

THE MEMBERS OF THE W. F. M. S.

Who are so faithfully holding up the hands of their sisters abroad in their work for His Kingdom, this little book is respectfully inscribed.

9THE smiling host of the Wagons Lits Terminal Hotel of Hankow bowed us out into the darkness outside, as we started in several rickshaws, one or two of them carrying hand baggage, for the Bund. On the way we overtook and passed the coolies who were carrying our trunks—carrying them in the typical Chinese fashion, slung from a pole; and also, quite according to the custom of the place, to the monotonous and rather painful groaning, or grunting, such as one hears continually during the daytime—the first groan being given by the man in front, and that being echoed by the man behind, usually with some difference in key between the groans. There is truly nothing that is ludicrous, in spite of the novelty of this accompaniment to work, and one's re10membrances of Hankow are colored in large part by this rather doleful melody of toil. Elsewhere we heard labor accompanied by truly a monotonous but a more cheerful variety of sound, more akin to song.

The boat was drawn up beside the wall which bounds the Bund and was the scene of much activity. There were but two foreign passengers in the first class, my mother and I, but there were crowds of travellers who were travelling after Chinese fashion, which meant being much more crowded, and I think, for the most part, providing their own food. One is struck in Chinese travel, both on train and boat, not so much by the terrible crowding of the native passengers as by the apparent courtesy, or at least resignation, with which they submit to it. So far as we saw, there seemed to be a toleration which would scarcely be shown by the European or American public for any length of time.

It seemed a little startling to be leaving for a voyage down the Yang Tze at 119 P.M., but it was somewhat in keeping with the departure of other means of conveyance in China, which, however, are more apt to leave at some early hour in the morning.

The starlight was beautiful, and under it one could distinguish the great broad sweep of the Yang Tze reflecting the lights of some boats anchored in the stream, and later the lights of Hankow as we swung slowly out into the current and turned toward the East.

We understood later why the start was made late in the evening, when the bright morning sunlight showed us the city of Kiukiang, with its Bund and its landing hulks, some of which are far out in the stream, and at which the vessels plying the Yang Tze stop to receive and discharge their passengers and cargo.

The cause of our going to Kiukiang was a long-anticipated visit to Dr. Mary Stone, known to a great many people in the United States both personally and through one or two accounts of her life and work which have appeared in print.

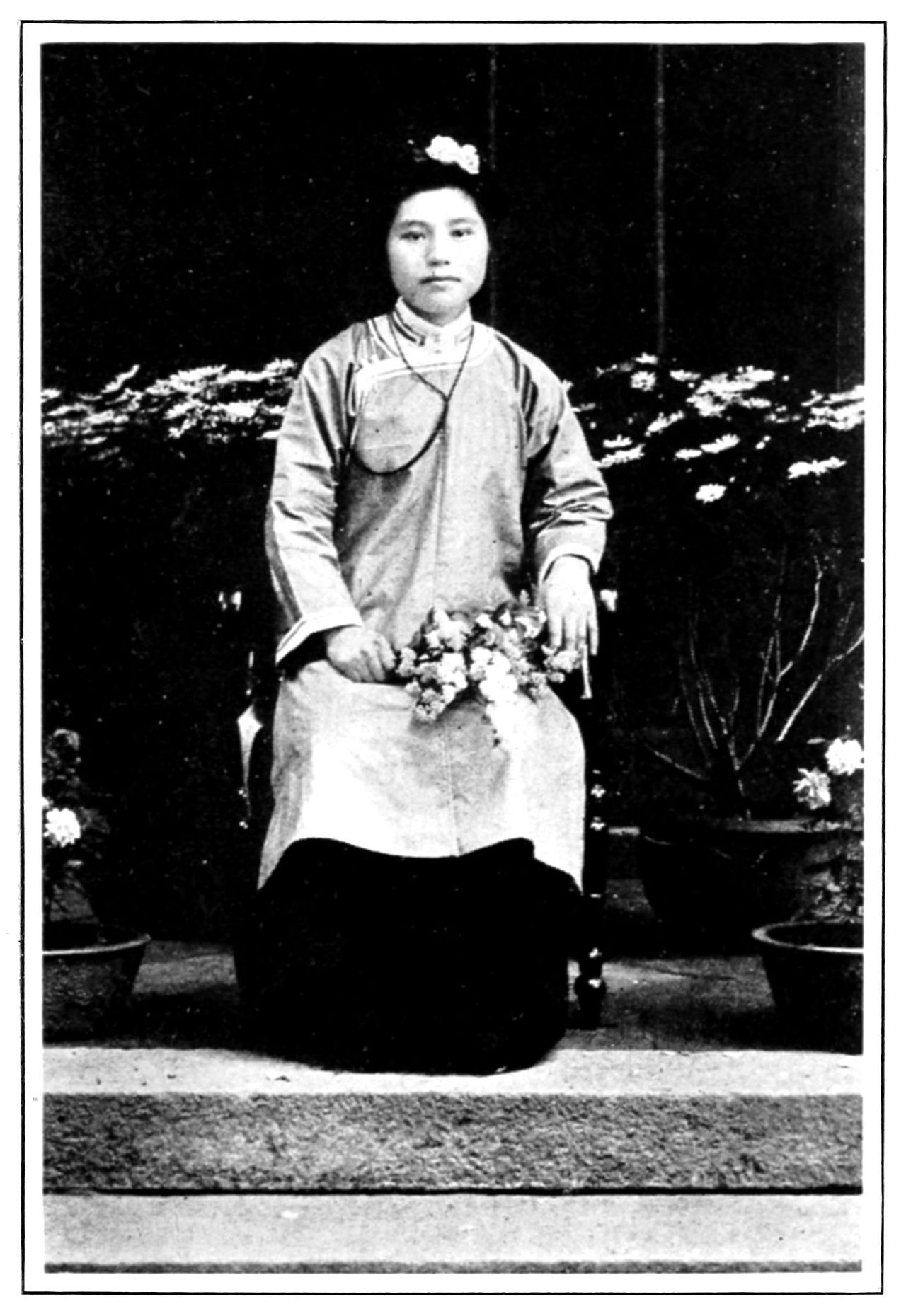

12Dr. Stone, for all her youthful appearance, has had considerable experience in all ways, though the home life from its start was that of a member of a Christian family, her father having been the first convert of the Yang Tze Valley and having become a preacher of the Gospel. On this account, and also because her mother was a Christian, the parents refused to comply with the usual custom of deforming the feet of their daughters, as was the habit of all their neighbors, and so the "Little Doctor" was the first girl of Central China to escape those months of pain as a child, and the subsequent lifelong inconvenience. She was taught by her parents in part, and also in the missionary schools, coming to this country in 1890, and being graduated from the Medical School of the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor in 1894, leading her class. On graduating, she returned to her country to undertake the conduct of the Danforth Memorial Hospital.

Dr. Stone had written that we should telegraph in advance in order that, as she 13expressed it, we might be "properly met." There was no one on the landing hulk, but this was at some distance from the shore and we thought probably some one would be over on the Bund when we reached there, so we took a sampan which carried us and our mound of luggage, and were sculled along over the rippling surface of the brown river which looked almost attractive under the bright sunlight of that October morning. We reached the shore and our luggage was deposited on the Bund, and a crowd of interested Chinese began to collect, but no familiar face appeared, nor any face that looked as if its owner recognized in us the possible friends of Dr. Stone.

The gathering crowd appeared to be mostly made up of porters, and it began to close in around us in a circle which seemed to be respectful though inquisitive, but was a trifle disconcerting. It occurred to me just before we reached Kiukiang that I ought to have been armed with at least some approximation of Dr. Stone's name in Chinese, and when we stood there, sur14rounded by this group of porters to whom we could not speak, and realized that a search for a friend in a Chinese city, where not even the name was known, would be a matter of no small difficulty, the perplexity seemed quite complete. There could not be, of course, many doctors in Kiukiang, so addressing the crowd rather broadly I said with a rising inflection, "Dai Fu," which in the Northern dialect means doctor, and then repeated it with an addition, "Stone Dai Fu," and then tried "Lady Dai Fu" and "Miss Dai Fu" in the hope that there might be some one at least who understood a word of English.

A look of great interest spread through the crowd, mingled with perplexity, and a policeman arrived on the scene and held the crowd back at a more respectful distance while I repeated my somewhat small repertoire to his no small mystification. It certainly was a situation that needed care to solve, and resembled the classical problem of the fox, the goose and the bag of corn. Of course, I did 15not wish to leave my mother in the middle of a crowd of Chinese in a perfectly strange city, nor did she wish to go off on an independent tour of exploration. It also was evident that it would be unwise to go off together and leave our baggage where it was, still more foolish would it be to sit on our baggage and wait indefinitely while the crowd increased, and yet more impossible was it for us to carry our luggage and, even had we been able, whither?

I then saw to my great joy the word "Contractor" on a building nearby, and went over, to find a Chinese standing in the doorway to whom I repeated my efforts about the "Dai Fu," also to his perplexity. It might be stated that the nearest approach to the word "Dai Fu" in the Central Mandarin is "Daw Fu," meaning a cook. No wonder the crowd had been mystified. Then I tried the word "hospital" and "sick people" with my new acquaintance in the doorway, because he said he knew a word or two of English, answering my rather despairing 16inquiry, and finally he said "Shü Ee Sen," and a couple of the porters, who had accompanied me on my little errand to the contractor's house, started back for the baggage, and the more energetic of them flung himself on all fours over the mound, feeling he was sure of the place where we wanted to go, and began to fight the other porters off and distribute the luggage piece by piece to his friends or relatives in the crowd. It approximated a free fight, but the energy and the persistence of this man won the day and, with one exception, he gave out the luggage pretty much as he pleased.

We then started up a street which we later knew was in the Foreign Concession outside the City Wall, a rather straggling procession of eight porters, my mother and myself. It was with a good many misgivings on my part that I followed the steps of our porters, not feeling at all sure that they knew where we wanted to go, but somewhere we were bound certainly, and with a mixture of alarm and interest we followed on, under 17the arch of the gate leading inside the city wall and then through such crowded, such narrow, such dirty and smelly streets! The head of the procession disappeared around a curve at once, and my uneasiness increased with the thought that the luggage might easily disappear down side alleys without the possibility of ever tracing it.

Such a strange combination, or succession of smells and sights as that was! Fish were being washed, food was being sold, food was being eaten in the little open-fronted restaurants, burdens of all kinds were being carried, merchandise of all descriptions was being displayed for sale, and everywhere was the color blue as the predominant shade for the clothing of the crowds. I spent my time in going ahead of the procession, counting the pieces of baggage, and then coming back to encourage my mother who was bringing up the rear. No conveyance of any kind was to be seen, and though Kiukiang has some chairs resembling sedan chairs there were none in evidence, and there was noth18ing to do but to pursue the hurrying footsteps of our porters, and indeed they did hurry after the fashion of the Chinese burden bearers, who feel quite truly that the quicker they reach their journey's end the quicker the load will be off their shoulders. We made two halts, one of them in a most unprepossessing place where a pond of dirty water suggested malaria and typhoid fever and seemed to be the home, or the particular environment, of a large and flourishing family of pigs.

My mother was growing weary. We had gone for a mile and we seemed to be getting out of the city (at least out of the most crowded part), and my uneasiness was growing considerably with the thought that we were possibly getting farther from our real destination and also getting to a place where no welcome English sight might meet one's eye.

Some brief moments of rest and we resumed our march again, and turned a corner leading up a small incline through rather an unpromising looking street or lane, where pigs and dogs seemed to own 19a considerable part of the thoroughfare, not to mention some rather untidy looking people; but over the top of some stone walls loomed the roofs of foreign style buildings, and I hastened back to encourage my mother for the last effort with the report that we were nearly there.

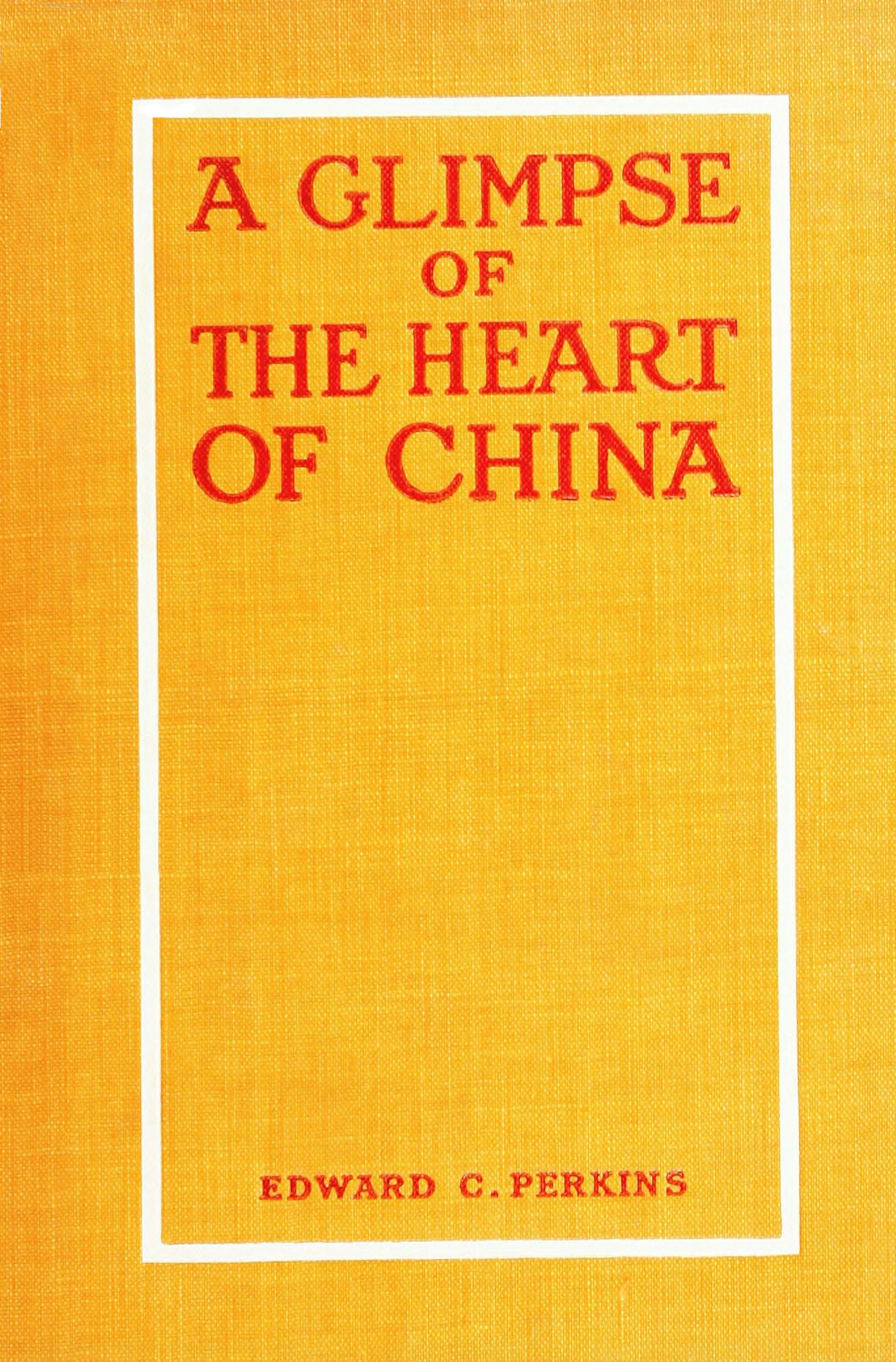

"With its two wings reaching out toward the gate"

It was with a feeling of joy and of great relief we saw the front end of the procession turning into a gate in a wall bordering the lane, and we ourselves followed through the first archway and then through a round opening in the second wall at the far side of a kind of entrance vestibule, to find ourselves in a place so different that it was almost startling; and perhaps almost as much as the change which the eye saw there came, too, a change in one's feeling, a restfulness, a peacefulness, which we were not alone in feeling, but which has been noticed by others who have crossed the threshold into that oasis of the Heathen Desert. Directly ahead a path led up to the gray front of the Hospital, with its two wings reaching out toward the gate, and on 20either side of the path was a row of bright colored chrysanthemums, for China as well as Japan is a land of the chrysanthemum.

We were met at the Gate House by a very sweet-looking Chinese woman, who greeted my mother with little inarticulate exclamations of distress, and we were escorted up to Dr. Stone's house. It appeared that Dr. Stone was not at home—had gone down to Nanking to the Annual Conference a day or two before, having started before the coming of the telegram which told of our proposed arrival. She had, however, conditionally ordered two chairs sent to the Bund, but we had failed to make connections with them, and the very attractive Chinese lady who met my mother was full of distress that she should have had the long walk up from the boat landing. She had a way of escorting my mother, holding her with her right hand under my mother's left elbow, and her left hand supporting her left wrist in a way which I fancy is a customary one in showing respect to Chinese ladies whose bound 21feet make them often rather unsteady. I have heard of one Chinese woman who virtually never took a step alone, but always leaned upon her maid, and, in general, it may be said that the women of greatest privilege have the smallest feet and are, therefore, the most in need of support.

This lady, who greeted us, was Dr. Stone's sister-in-law, who spoke a little English and understood much more, but was rather timid about speaking at all with the feeling possibly that our ears would be offended by mistakes; but, with her English, as with that of two or three others whom we learned to know at Kiukiang, the softness of intonation and the sweetness of voice could not by any means make errors sound at all objectionable. On the contrary, I must confess to being not a little attracted by the odd order of words and the interesting changes of our customary use of our language.

The path to the doctor's home had led us around the East Wing of the Hospital, up a flight of steps, along a walk that was 22bordered on both sides by a lawn across which, at a little distance, began the flower garden of roses and chrysanthemums, quite a mass of blossoms, although the month would mean anything but such a display with us in America, to where before us stood the gray building, the present—and a memorial present—to the Compound, the home of Dr. Stone and Miss Jennie V. Hughes.

Before we reached the Compound the man who had successfully corralled our baggage had stopped to impress me with the fact that he was "No. 1 Boy," which words he knew, and therefore I inferred from gestures and a few rather inarticulate phrases, that I was by no means to pay all the coolies alike, but to turn over the funds entirely to him and let him pay the rest with the "squeeze" for himself, according to the ordinary Chinese usages. There was quite a little doubt in my mind as to how much the porters ought to receive. I was perfectly sure that they ought not to be given all they asked, and finally the amount which was paid, al23though less than they seemed to feel was necessary, made them go away in a state of great delight, and as we learned afterward they received many times more than the usual few cents, the customary wage for carrying a load for so considerable a distance.

Such an atmosphere of welcome as the house itself seemed to give! Such a homelike place as it was—all of it! We turned to the American side of the house (there being a Chinese side to the left of the front door), and came into a delightfully comfortable sitting room with a library seen through the large double doorway, and just here let me add parenthetically that the thought began to dawn on my mind that we were in the presence of the "Missionary luxury" which one hears about in this country. If it is a confession, let me make it, that before the return of our hostess I took occasion to make something of a mental inventory of the furniture and ornaments, in order to be sure of my facts, and as I think one, who knew Dr. Stone better than I did then, would readily im24agine, the result was that I realized how perfectly fitting all the appointments of the home were—by no means luxurious—interesting because foreign to us, but not costly, and yet all arranged and placed with such a fine sense of the artistic, and the convenient, that it really gave the impression of a beautiful house. Those who come to know the many-sidedness of "The Little Doctor" will realize that quite overshadowed as it is by more important and more beautiful characteristics, there is a true sense of the artistic, too, in her rounded character.

We went upstairs to our rooms shortly. One could not help being delighted with it all. My mother's room looked out in one direction toward a venerable pagoda which was bushy with green growth, almost from bottom to top, there being a particular mass of shrubbery on its top roof.

My room looked out over the rose garden, across the Compound Wall on the far side of which lived an assorted family of pigs, and a little shanty which looked 25hardly nice enough for their home, but which in reality was the home of their owners. I recall seeing one of the pig family, one of the largest, disappearing into the house. I expected to see his immediate exit, but was disappointed.

Nearby were trees, on a branch of one of which a man occasionally brought out a bird in a cage early in the morning and stood off to listen to it sing a melodious, liquid, forest-like song, some sort of thrush one might think. A fondness for birds is one of the noticeable traits of masculine China, and one sees many of the men in Peking carrying a bird cage and its occupant as a man in England or America would take his dog as a companion. Beyond this nearest menage were some low-lying roofs, and farther still quite a sharp rise of ground surmounted by what I took to be a little hilltop shrine. There was a constant ascent and descent to and from this little place, and it seemed to me that probably these were worshipers. It proved, however, that it was a kind of observatory, and that people who went to the top 26went there merely for the view. Quite astonishing again and rather revolutionary to one's ideas of the very matter-of-fact viewpoint that a Chinese has of the world.

The following day, which was Sunday, there was a perfect crowd on the hilltop and some surrounding high ground all day. I watched them through a pair of field glasses, but could see no sign of worship, and fancied that it must be rather desultory. Just beyond this little observatory there was, though not as high as it, the gray battlements of the ancient City Wall and over the top and much farther away one saw the blue hills on the far side of the Yang Tze.

The bed, placed somewhat in the middle of the room, assigned to me, gave the impression of airiness and a rather summery feeling, which was heightened by the white mosquito netting. This latter, even in November, was most important, and I must confess to a certain feeling of disquietude at seeing specimens of the mosquito family, the possible donors of an attack of malaria, resting on the walls.

27In another direction the windows looked across the pretty lawn to the hospital, which was quite close by, and on opening the shutters at night I always saw the subdued light in the hospital, and usually the dim form of one of the nurses going about on her ministrations to the sick, and it gave one the sensation of pleasure and gratitude to think of a needed work like that going on for twenty-four hours a day.

Dr. Stone's sister-in-law soon withdrew, and we were left to unpack our things and to take possession, which was a pleasure, inasmuch as the house had such a homelike atmosphere, and we had been spending so many days in cars and steamboats and hotels.

An American lady of prominence who has visited widely in China is responsible for saying that Dr. Stone's house is the most homelike home she knows in that kingdom. Somehow the thoughtfulness and the winsomeness of our hostess seemed to anticipate our coming and be really an entity in the home almost as if we had an unseen hostess.

28Before very long the shy figures of two rather slight Chinese boys appeared, and in one of them I recognized, through photographs sent to America, one of Dr. Stone's practically adopted boys, Mo Lin Wu. The house is the home of four boys, aged from seven, I should judge, that is, Wesley Mei to Leslie, the oldest, about thirteen.

The personnel of the four brothers is interesting, and particularly interesting is the fact that from very different origin they are being brought up in a most harmonious manner, quite as if they were really brothers. From my observation, it seemed to me that there was less difference of sentiment among them than is usually the case in a family of boys. Luther Stone is the doctor's nephew, the son of a brother who died a number of years ago, and also the son of the head nurse in the hospital. Something there is about him which reflects the attractiveness of his mother. Wesley Mei is the son of a young widow, Mrs. Mei, who is one of the head teachers at the Knowles Bible Training 29School. This school is at present separated from the hospital by a considerable distance, but when they get into their new quarters it will be directly across the street. The mother, Mrs. Mei, has also a little girl who lives with her. She is so devoted to Christian work that she goes on patiently with her labors in Kiukiang for $5 a month, despite the fact that friends and neighbors have expostulated with her for not taking positions in the Government Schools. She has had offers which would mean very much more money, but she gives these up to keep on with her distinctively Christian work; and the faith which believed that her work would be rewarded and that the children would be cared for has been justified from the fact that one person is supporting the little Wesley now and another stands waiting to do so if necessary.

Leslie, the oldest of the four, was a famine child, and came under Dr. Stone's care in a very lamentable condition, such a condition, in fact, as is rarely seen in this country, except by those who see the 30cases of marasmus which usually find their way to the hospitals. He is now a sturdy boy and looks the most rugged of the four. Mo Lin Wu is related more distantly than Luther to the doctor. He is the most energetic of the four and originates most of the plans and games. The doctor has wished their spending money to come to them in a way that would teach them something about work, and so promised them a small copper coin for each pail of water which they would carry for the rose garden. It appears that the bright idea started in the head of Mo Lin to enlist the little girls of the girl's school in this financial enterprise, and they received one copper coin for every ten pails they carried, which left a handsome balance for this young contractor. Dr. Stone discovered this arrangement and the matter wore an altered complexion after that.

About one o'clock the sound of some Chinese gongs, or rather bells, told us that lunch must be ready, and we went down to find the dining-room furnished with a high table, and two places set, and in one cor31ner of the room a small table with four small chairs and some three or four little bowls in the middle, while a bowl and two chopsticks marked the places of the four youngsters. The latter, who were already seated, were waiting in respectful silence, probably, as I supposed, for some one to say grace, and after that they started to eat their rice and some other food, partly fish, which was contained in the central bowls. At intervals, one or the other rose from his seat and disappeared through the door leading to the back hall, which we later learned was on the road toward the kitchen below, where the small bowls of rice were refilled and brought back in triumph to be flavored with the fish and sauce in the other bowls.

We could not talk with the very thoughtful and efficient Chinese waiter who looked a model of politeness and friendliness, nor could we talk with the boys, for it was not for several days that we learned how well they understood English, and my mother recalled the fairy story of the traveller who wandered 32through a forest to find an enchanted castle where he was waited on by invisible servants, no part of whom might be seen except their hands. It seemed almost like a house of hospitality with only the hands to help. The dining-room has in it some interesting china, Kiukiang being the home of some kinds of pottery and porcelain, and these being the presents of some grateful patients, I presume, give a very pretty effect to the sunny room.

The library, which adjoins the dining-room, has quite a number of English books, and not the least of the collection are a number of shelves of up-to-date medical books, given by the late Dr. Danforth, of Chicago, added to from time to time as new works have come out. To me, that was a source of great delight, and I anticipated an unbroken chance to study, as it did not seem to me likely that there could be very much in a practical way to be done to help our hostess when she should return.

Somewhere along the middle of the afternoon Dr. Stone's sister-in-law knocked 33at my door, and, after some difficulty, I made out that she would be much obliged if I would go over to the hospital to see a patient. The mixture of English, with its interesting accent, together with an effort to be most courteous, had the result of placing the words in a singular mosaic, so that I really was not sure what was wanted, but finally realizing that I was asked to the hospital, I followed with mingled feelings, including very prominently one of alarm at the thought of seeing a patient who could not speak English, and who might have something very disastrous the matter with him, and, along with this, was a sense of exhilaration at the thought of really being on the threshold of something like medical missionary work.

We walked through the long hallway which traverses the main building of the hospital, and out of a door at the other end into a small side court, where the building stands that serves as their isolation ward. There were no contagious cases in it during our stay at Kiukiang, 34and, under such circumstances, it is used for some of the students of the William Nast College, inasmuch as men could not well be admitted to the hospital proper.

I followed my guide into a room and saw a young fellow lying in bed with his head bandaged, leaving little more than the eyes exposed. Of course, it was evidently a surgical case, and I was shown some water and soap and a towel was brought for me to scrub up. My thought ranged around vaguely for a necessary antiseptic, but I supposed that their technique did not feel the need of bichloride of mercury, and so, after a good scrub of soap and water, I started to examine the patient. My dismay was complete when a moment later the head nurse, Mrs. Stone, arrived with a basin of bichloride, and, in fact, this so disconcerted the visiting physician that he almost forgot all the surgery he had ever heard of, and was simply covered with mortification.

The case was one of an infection of the lower maxilliary region, but an examination both there and inside the mouth 35showed no treatment necessary other than the incisions and iodoform dressings that had already been in place. The infection had somewhat invaded the left eye, and that was a little the better for the washing out with boracic acid, which it received. However, the case was doing well, and the dressings were put on again, with the statement that things seemed to be going favorably. But the visiting physician retired in much confusion, and confided to his sympathizing relative in the house that all chances of future usefulness in the hospital were gone for good and all, and that an impression had, without doubt, been left that he had never seen anything in the line of surgical technique.

Great was his joy, however, later in the afternon to have the same courteous and somewhat ambiguous invitation to go to the hospital again, this time to see a little child about 10 days along in tuberculous meningitis. The mother was there, such an anxious-looking mother as she was, too, but, of course, it seemed best to tell her at once that the case was a very se36vere one, and in the light of the probable diagnosis was also to be a fatal one. I advised her, through the interpretation of the head nurse, to keep the child in the hospital for a while, however, until we could be more certain, feeling the added responsibility of its being somebody else's hospital, and yet wishing her not to feel that the child's death was the fault of the treatment there, because the place is a witness for Christ.

On returning to the house I found my mother receiving a call from two very attractive Chinese ladies, who it appeared were the two heads of the Knowles Bible Training School, and whose names were Mrs. Mei and Mrs. Lan. They understand English quite well, and speak quite intelligibly, too, and they were asking my mother to speak at the Sunday School service the following day, a privilege which was finally delegated to me. It should have been mentioned that at 4:30 the bells rang downstairs again, and we went down to find the table set with afternoon tea, a meal in which the small 37boys habitually did not share, or, after the return of Dr. Stone, shared in a rather desultory manner with nibbles of cake or cookies.

In the home, at the head of the stairs, is a square upper hall, and a desk where two people may sit, one on either side. This desk later was associated in my mind with visions of the Little Doctor sitting writing and writing after midnight to friends in America, and also a sort of a nightly council of war held with her on matters medical, cases visited and treated during the day, which the rushing hours of the working time prevented from being fully talked over earlier, and, indeed, that council came to be one of the pleasantest features of the day. But on this first Saturday evening it was there that my mother and I drifted quite naturally to read and write with a lamp standing between.

Sunday dawned, and with it there came a wish to go to the morning service, but the question was—where? I started out to find some church, feeling sure that there must be one somewhere, and, by good for38tune, met Dr. Stone's sister-in-law, who was in a chair with two chair coolies as porters, going to a maternity case. I tried to follow some people whom she indicated as on their way to the church, but these, being two ladies and a girl, seemed to feel that I ought to walk in front, which I was rather loth to do, because I didn't know the way. However, at each turn, I looked back to receive the direction by the wave of the hand, and finally reached the church which it appeared was largely for the Rulison School for girls and the William Nast College for boys and young men.

Few audiences one could imagine are so inspiring to face as the audience of that church with its four or five hundred boys and girls, the boys and young men being to the right as one faces the church and the girls to the left, and the students of the Knowles Bible Training School mostly in the gallery at the end of the church. The missionaries were almost entirely away at conference at Nanking, and the sermon of the morning was preached by one of the professors, a Mr. Tsai, who is a devoted 39and consecrated Christian, and one of the native teachers having, I think as a specialty the subject of mathematics. Doubtless he cannot confine himself to that subject as the exigencies of missionary work require some versatility. Dr. Isaac Headland, on being asked during his last visit to America, what chair he occupied in the Peking University replied, "Chair! Why, I have a whole bench."

About noon on Sunday the comparative calm of the lane outside the hospital grounds was sharply broken by the sound of an approaching storm of firecrackers. We listened for some moments in surprise and doubt, and then concluded that possibly the Little Doctor was returning home. She has been escorted back to the hospital in this way, so that we felt quite sure that her arrival was being announced, but when we reached the gate house and entered the atmosphere heavy with smoke and an odor reminding one of our own Independence Day we learned that it was one of the nurses who was returning from a maternity case. It appeared that a lit40tle boy had arrived in the family and that the friends and relatives were so pleased that they had escorted the nurse all the way home in order to show their appreciation.

It is needless to say that had the arrival in the family been a daughter no such demonstration would have marked her advent. We, of the Western World, are more or less perplexed at the very great contrast of feeling which there is in the minds of parents between their boys and their girls, and the many instances, which seem so terrible in our sight, of the doing away with the little girl babies by exposing them in the road or throwing them into some pond, which is constantly done.

The matter of such a contrast is not so hard to grasp, however, when one of the fundamental beliefs of the Chinese is understood. This may be styled a religious belief, inasmuch as it takes hold of the world of the unseen, and is connected with their worship.

Their thought is that they who pass on into the spirit world are fed and clothed 41by donations from this. In other words, that the unseen is dependent upon the seen rather than vice versa. So every one who goes out into that unknown country believes that he must receive offerings of food and offerings of clothes from people who either live or shall live. The only one rightfully to present these offerings as the priest of the family is one of the male decendants, and those who leave no male decendants behind can expect to be nothing but mendicants forever and ever in the spirit world—a desolate outlook indeed—and one can scarcely be surprised that with this belief firmly in mind the wish of all hearts is to be represented by a son or as many sons as possible. It is further true that the girls will very literally belong to another family upon their marriage.

One sees almost constantly the stores where articles are sold for the benefit of those who are supplying the needs of their relatives in the land of shades; and in these shops the long strings of small hollow pasteboard boxes covered with gold and 42silver paper hang from the ceiling in rows quite bewildering to the uninitiated, and one may see at times some man travelling homeward with quite an armful of these pasteboard boxes and paper money and clothing which he purposes to burn. The clothes which are thus introduced into the world of the unseen are pieces of paper with a printed pattern on them which, when burnt, are believed to turn into beautiful and attractive brocades in the other world. In the case of royalty, and doubtless with people of rank, the offerings are of real silk and other articles; the funeral of the late Empress Dowager having been the occasion of the burning of a vast quantity of valuable silks, etc. But by far the great proportion of these offerings which are made are merely an imitation of what the presents are supposed to become later.

The offerings of food are also of two kinds—there may be the presentation at the graves or before the ancestral tablets of real articles of diet, or there may be merely imitation ducks or pigs which are 43rented for the occasion or left for some hours at the grave. The offering of the real food is, I believe, much more common than the burning of real clothing, inasmuch as the shades of the departed are supposed to only take some sort of spiritual nourishment from the food which does not in the least prevent its value to the family later on.

And so it comes about that the girl babies early begin to realize that their position is not at all on the same level as that of their brothers.

Sunday school came early in the afternoon, and the evening service somewhere along 7 o'clock, there being a service down in the Foreign Concession at 6 o'clock, to which I went with two or three of the missionaries who were not in Nanking. The sermon there was preached by a man who belongs to the China Inland Mission, and whose income is something like 200,000 pounds a year, and yet his own life is on so simple and frugal a plan that he makes his journeys in the uncertain weather, hot and cold, of China, on 44foot from place to place so as to help set a standard and help maintain a simplicity of life for the native preachers.

Evening came again, after a day which seemed much shorter than the previous one, although by no means devoid of incident and blessing, and again my mother and I sat in the upper hall at the two-sided desk. It must have been 10 o'clock, and the house was very quiet, the brothers having crept away to bed, when all at once there was a scurry of feet on the stairs and, smiling joyfully, our hostess arrived. She had taken the first boat back from Nanking on the receipt of a telegram telling of our arrival. Such a pleasant, such a delightful, meeting as that was. We talked and we laughed and we exchanged experiences at once, and all things were much to her amusement, and so the living in almost a stranger's home in a more strange land came to an end, and we felt the actual presence of the most thoughtful, the most gracious, hostess.

The following morning the bells rang again for breakfast, and we went down to 45feel the house under command of its mistress again, and the breakfast began with John Wesley's grace:

"Be present at our table, Lord,

Be here and everywhere adored.

These mercies bless, and grant that we,

May feast in Paradise with Thee.

Amen."

in which the small boys at the little side table joined. The hostess of the home speaks beautiful English, idiomatic and correct.

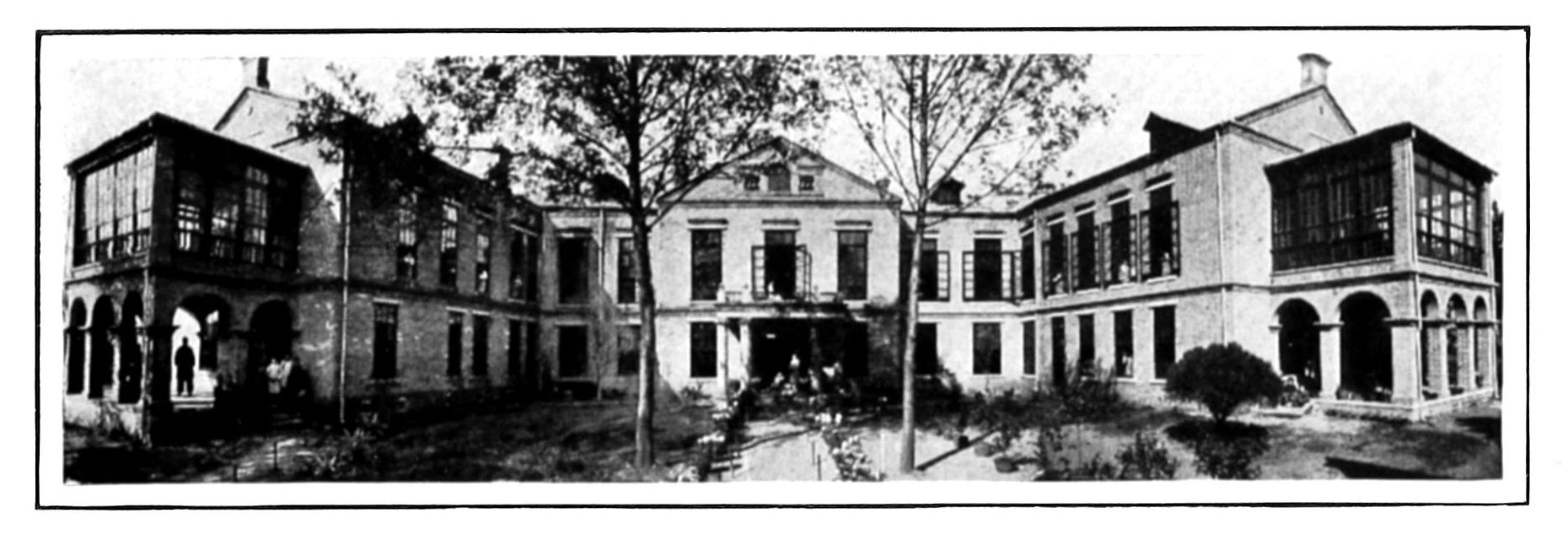

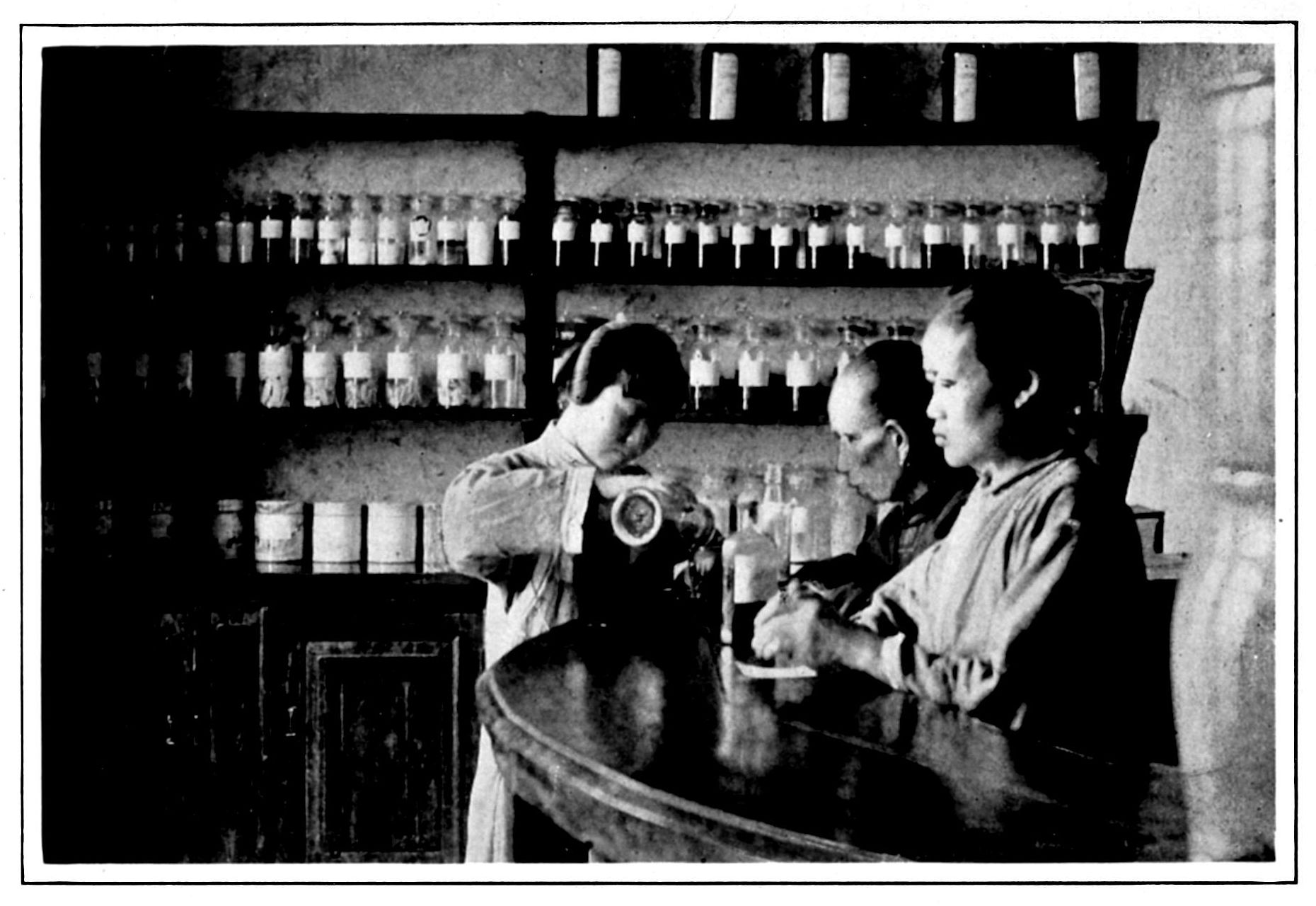

"Quite a number of the patients came at the summons of the bell"

After breakfast we went over to the hospital and attended the morning prayers, which service was announced by the somewhat penetrating sounds of a gong which hangs in the doorway of the room that serves as chapel and as the dispensary waiting room. Quite a number of the patients come at the summons of the bell, and the front bench was occupied by a row of very bright appearing and very neat looking nurses, dressed in blue.

It was an interesting sight, the evidences of sickness in the way of bandages and expression were plainly to be seen; 46but the Bible and the singing of the hymns, the organ being played by the "Little Doctor," and the prayer, and something of an address, were all attentively listened to and joined in, and the whole impression was one of uplift. Some of the dispensary patients had already arrived, and after prayers on that morning, as on others, one could see the "Little Doctor," with her rapid diagnosis and directions for treatment, with the writing of prescriptions, working busily in the treatment room, from which the patients emerged to go directly across the hall to the drug room, where medicines were given out over a counter.

"Where medicines were given out over a counter"

Dr. Stone's work is so arduous in just taking care of the women and children that it is impossible to think of caring for men, with the exception of an occasional student from the college, and yet they come, and, in cases that can be treated, are not turned away. That morning a man arrived who had a double pterygium. We had a look at him out on the hospital porch, and the "Little Doctor" turned to 47me in a quick way she has, and asked, "Will you do it?" This was like lightning out of a clear sky, and the visiting physician, with a few pages of text books, but little experience behind him, felt almost weak in the knees, as he replied that he would if the doctor in charge would be present at the operation. The man was told that he was to be "operated," and he showed his joy and gratitude in no uncertain gestures and expressions, and the visiting physician felt more like a murderer in disguise than anything else, and read up with some trepidation and with great intensity two operations for removing pterygia as set forth in a surgery in Dr. Stone's library, and, incidentally be it said, found it difficult to sleep during the night which intervened between the promise and the operation. The man was told to wait at the gate house, and subsequent to the operation was lodged and cared for there, evidently much to his satisfaction, and there he made a good recovery, Dr. Stone having assisted at the operation.

The atmosphere of the whole Com48pound, from the Gate House to the Inner Shrine (which we would suggest as the "Little Doctor's" own heart) is a place of consecration, and every part of it provides its missions of helpfulness. In the basement of the home was a little schoolroom with twelve small desks and a teacher's platform and desk, and in this the four brothers and some six or eight other boys who live in the Compound, and whose parents are employed in one way or another in the hospital work, go to school. It happened that the teacher was sick at the date of our visit and the scholars, although having good intentions and staying in the schoolroom part of the time, quite teacherless, trying to keep busy were really having a prolonged holiday, and at most hours of the day might be seen playing about the garden or on the southeast porch of the hospital.

Farther to the rear in another part of the basement in a storerom is the play place of the four brothers, and each has there a little impromptu house made out 49of pieces of wood and boards, picked up who knows where. These little houses are the home of much joy and delight and the resource of rainy days. Each one of the brothers has his own little house in which are scraps of pictures pinned up, and chipped cups and saucers, etc., etc., a medley of small treasures and curiosities with the possibility of a large element of the make believe. Some one has recently written about the modern toys for children, the mechanical toys that are beyond the understanding of their owners, comparing these with the coach made out of two chairs, or the train made of blocks where the proud proprietor is the owner and engineer, the driver and the fireman, the conductor and the passenger and motive force all in one, with the most delightful range of fancy and freedom of thought; whereas the mechanical toy leaves him but a little child in the midst of the hearth rug. Certainly, these Chinese boys each have a most ideal playhouse and many an hour is spent there.

Speaking of schools there is also a lit50tle girls' day school near the Compound wall which had upwards of 30 scholars while we were there. I counted upon one occasion 33. The walls of this school are hung with some of the Berean Sunday School lesson pictures and have also a blackboard or two. The teacher is a very sweet-faced Christian woman who apparently has not much difficulty in the way of discipline. Beside her own desk on the platform there stood a little basket something like a small clothes basket and in this her little baby lay. I do not recall having heard the child cry. It is probably a sort of a model little Chinese baby, and apparently the girls are not like the scholars at Mary's School, who were made to laugh and play.

Without looking forward to the future this school to-day sends out many lines of influence. Dr. Stone told us of a little scholar of the school, who came to school for a number of days in tears. Her teacher asked her what the trouble was, and had as a reply that her father had beaten her. On being asked why he had beaten her she 51replied it was because she tried to tell him about Jesus, and so the teacher told her that if she could not tell about Jesus at least she could "live Jesus," and that the thing for her to do was to be so bright around the house and so ready to run errands that she would be witnessing all the same. It was only two or three weeks before her father said to her one day, "Come here little girl. What has happened? You are so different now from the way you used to be." The child replied timidly, "But you won't let me tell you." "Yes, I will," he answered. "I want to know all about it"; and so her longed-for opportunity came. Who shall measure the influence of the children who go from the day school with their knowledge of a living God into those places which, with apology, we might call homes. If one may judge at all by the appointments of a Chinese home there must be but little home life.

On one of the days of our stay in Kiukiang a woman came to the hospital to ask that some one might go down and see her son, who was ill. Dr. Stone being 52very busy I took the call and followed the woman down the roadway outside the hospital Compound, the big alley which had become quite familiar by this time, and turned off not far from the hospital, going through a gate and then through a series of little passages or hallways or courts, or rooms, round corners and through doorways in a manner that was perfectly bewildering, and more than that, gave one the impression of a bad dream, for one could not tell whether he was out of doors or in a house. We passed numberless people. One place which seemed to be part of a court had in it some men who were weaving, and in another place there were some men who were having a meal together, although it did not seem to be any particular meal hour, and these stared at us curiously, and at last, without any doorway, but coming under a covered place, we turned a corner, and the sick room, if it might be called that, was before us. The bed was most unsanitary, being set into the wall. The place was dark at best, and two curtains which hung before the bed made 53it darker yet inside, so that I went to the wrong end of the bed to find the patient. On turning around I noticed that the place where we were, which could scarcely be called a room, was full of an interested but respectful crowd. On one side was a window largely of paper, with a little square of glass in the middle, and through this one could see the faces of a number of people besides who could not perhaps get a good view inside the room. The patient was very ill. It proved to be a case of advanced pulmonary tuberculosis, and the little medicine case which I had brought had nothing in it which could be of service there. The crowd wanted to be useful evidently, and there being many of them I found that I could communicate with the sick man through them. I turned to them and breathed deeply, and pointed to the patient who was now sitting on the edge of the bed, and they told him that I wanted him to breathe deeply, too, for the purposes of an examination.

During the examination I was so unguarded as to sit for a few moments on 54the edge of the bed, and on rising was brushed by a sympathizing member of the crowd in order to remove one or two little visitors who had fastened themselves on my clothes, and, it might be added parenthetically, that the visiting physician returned with all kinds of forebodings and sensations of alarm and fear, at the thought that he might bring into that charming home some souvenirs of the occasion. The crowd were informed by signs that there was nothing in the medicine case for the man, and an effort made to make them understand that the mother of the sick man was to return with me to the hospital in order to get some medicine there.

As it happened I was equipped with about six Chinese words, two being "tong ba," the former meaning pain, and the latter being spoken with a rising inflection, probably a kind of an audible question mark; the words "kaischway," which meant hot water, which phrase was useful in getting some water for washing the thermometer, and the name of Dr. Stone 55in Chinese. This last phrase was employed in a general way to signify the hospital and that a return thither was necessary, but the crowd misunderstood it to mean that I wanted the "Little Doctor" called in on consultation, and a swift messenger was started for the hospital, but called back and detained while the efforts to induce the mother to go with me to the Compound were resumed. The crowd was confused, the mother was perplexed, evidently my sign language had broken down, and my very vigorous beckoning to the mother seemed to convey no idea at all. No wonder! When one wishes a person to follow them or come to them one uses a sign which with us means a farewell, a shaking of the hand as children say "good-bye." At last, however, the matter was cleared up, and the woman came along to the hospital to receive something that would make the last days of her son less suffering.

A good many of the "Little Doctor's" calls for help outside of her hospital and dispensary practice are in maternity cases. 56She told of a man who came one dark, rainy night and asked her to go across the Yang Tze and six li (two miles) into the country to where his wife lay ill. It appeared that the case had been in need of medical aid for four days, and surely the horror of cases like this, cases that are impossible to the native efforts, should make us of the Occident stop and think, and remember the terrible hours of pain and the hopelessness and helplessness of the situation for all concerned. The man who came to Dr. Stone went down on his knees in Chinese fashion, and, not on that account, but on the Lord's account, the "Little Doctor" said that she would go.

She took one of her nurses with her, and the two chairs, with their chair coolies, started on their long trip. One should not fancy the streets of Kiukiang as lighted by electricity or street lamps. In fact, to find one's way home from a nearby place without a lantern would be almost impossible, except to one who was entirely familiar with every step of the ground, and the little lanterns which the chairs carry 57throw but a dim light into the surrounding darkness, and one should not fancy either the Yang Tze as a river easily crossed and recrossed by ferries, for its broad stream is neither spanned by bridges nor crossed by anything like an American ferry service at or near Kiukiang.

The party went their six li into the country, and the man began encouraging them by saying, "Almost at the place—just there," etc. The party pushed on ten li, and the man kept reassuring them with remarks of the above nature. Fifteen li they went, then twenty. The chair coolies began to grow cross. They slipped in the mud, the rain was falling, and it was dark; twenty-five and thirty li they went, still the man assured them that they had almost reached his home, then thirty-five, and the man's assurances were as confident as ever, and at last, at the end of forty li, through the dark night and over such paths as we should scarcely want to travel here in this country by day, they reached the home of helplessness.

58The woman who had come in to lend the best of her aid had infected eyes that were running with pus, and the house was full of the neighbors—full of men. Dr. Stone had to be firm in demanding that the helpers' services should be at once dispensed with, and then she insisted that the visitors should withdraw, which they declined to do. The house owner was afraid—they were his neighbors, and might prove ugly afterward. They even sat up under the rafters of the house. Dr. Stone washed her hands preparatory to work, and then turned to the audience and said very firmly, "I have begged you to get out, and I have told you to get out, and now if you don't get out (this accompanied by an appropriate gesture) I am going to splash this all over you." This had a magical effect, they almost fell over one another in making their escape through the door, very likely feeling that some sort of spell would accompany the process. The doctor then relieved the situation and saved the woman's life, and, since there were none of the neighbors as witnesses, the 59story spread abroad that she cut the woman all to pieces, and then sewed her all together again.

The intrepid Little Doctor and her nurse then started on their long journey home. Of course, the expedition had occupied much more time than had been anticipated, and the lanterns which were on her chair and that of her nurse had been used for light at the operation, so that before they got back to the Yang Tze again the lanterns went out and they were left in pitch black darkness. Further advance was impossible. The chair coolies spied nearby a little hut which proved to be a pig-pen, and they crawled in and pulled down the straw over them and slept with the pigs all night, while the Little Doctor and her nurse leaned up against the sides of their chairs and caught what rest they might till dawn, when they could proceed on their journey again.

The cases which came to the dispensary were sorely in need of help. This was, I think, the invariable rule. Such cases they were as do not often come to the observ60ance of physicians in this country, and some familiarity with the dispensaries of four of the large hospitals in New York City has almost failed to show such need as the Little Doctor sees continually.

One small boy was brought whose hands and some areas on his body were in a pitiable condition. He had suffered from some severe burns, and the family, in their effort to do the best thing for him, had made a mixture of oil and ashes which was perfectly black, and which had been liberally smeared over the body and hands so that the hands were almost as black as a coal except where pus and blood were dripping out. It might be said, with due justice that ashes and oil are not nearly so bad as some other modes of native treatment, although rather bad enough from our viewpoint. It was quite astonishing to see what a more enlightened treatment could do even in twenty-four hours, and the condition of things the next day was surprisingly good.

One child, I recall, had a head that was almost one mass of sores, not entirely ex61cepting the face. One man, who called rather contrary to the understanding of the dispensary, but in great need, had been attacked outside the city by some feline which he called a tiger, and very possibly it was a tiger, for we heard the mountains within sight of the Little Doctor's residence are inhabited by these animals. He had some bad lacerations of his scalp, due probably to the teeth of the animal. One of these long furrows reached to the corner of his right eye and he had only narrowly escaped having that torn out. I counted twenty claw marks on his left arm. A friend had come to his assistance and killed the beast, and then he had waited for nine days before coming to the dispensary, so that there was a very extensive infection of the scalp wounds.

In the Dispensary waiting-room, which serves as a chapel for the morning service, the waiting crowd is addressed or perhaps usually talked with more familiarly by one or more of the four Bible women who are in constant attendance on the work 62of the hospital. One of these is the Little Doctor's earnest and enthusiastic mother whose story of rightful ambition to learn to read Chinese, although a grown woman at the time of her beginning the work, has appeared in print before, and perhaps needs no repetition here, but her ambition now and daily effort is to learn English in order to help her grandson, Luther, and the other "brothers" whom Dr. Stone has as her children in her home.

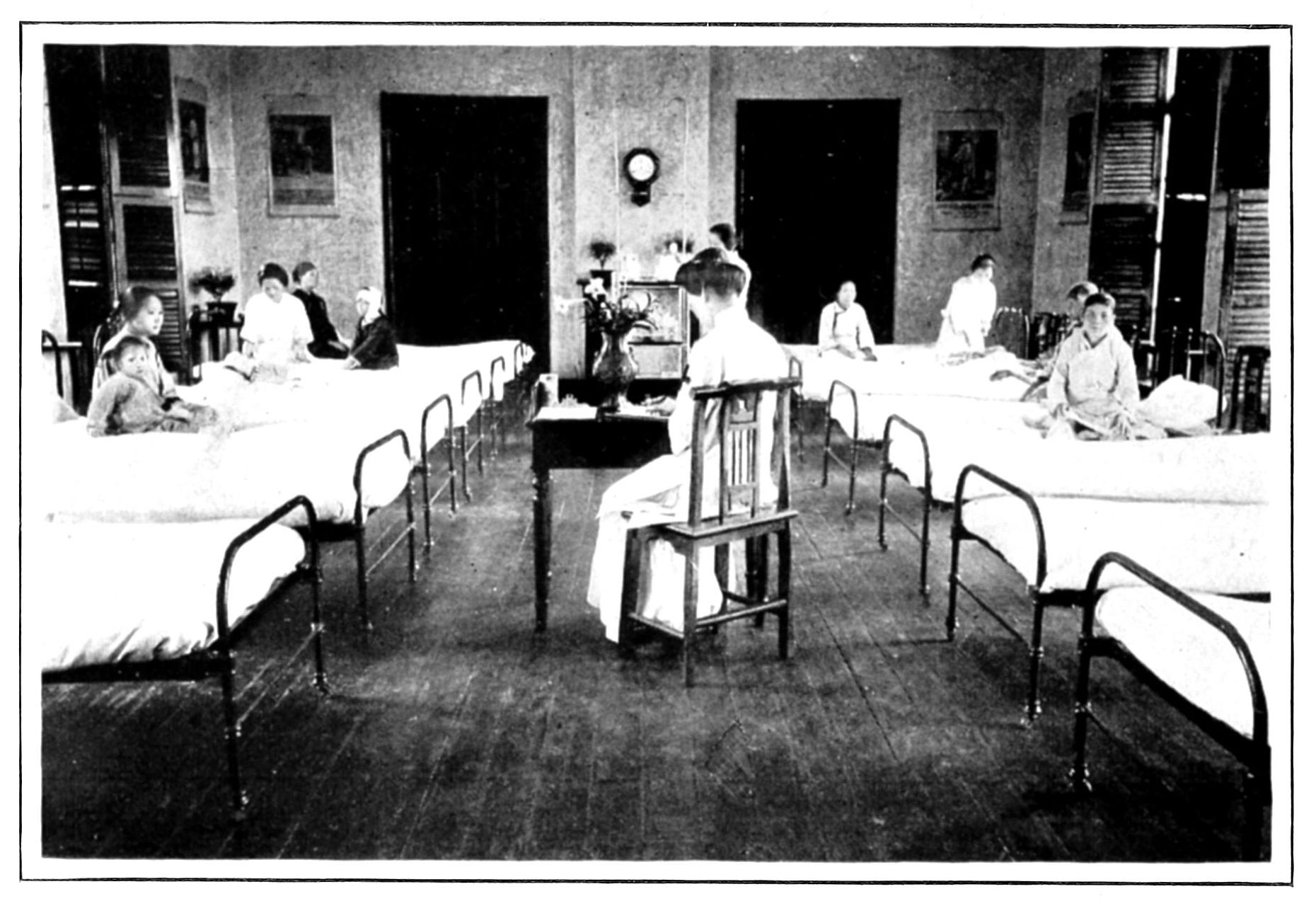

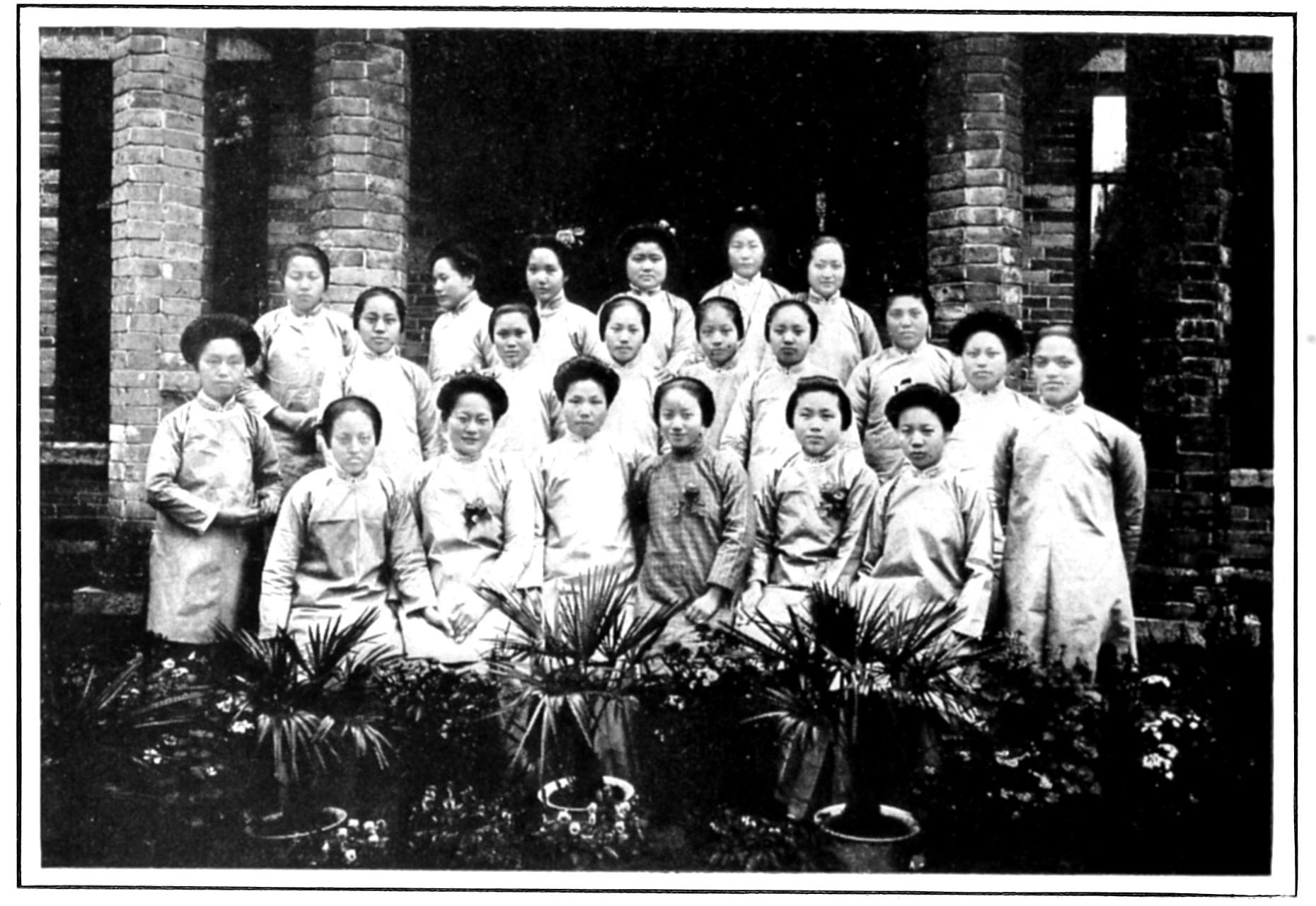

The nurses, too, are strongly evangelistic in their thought and effort, and even to one who could not understand the language the atmosphere of Christian harmony and the remarkable lack of friction in a place so busy and so continuously full of problems was very noticeable. One could see the patients brighten as the Doctor went her rounds, and somewhat the same temper characterizes the lives of her 20 nurses who rejoice exceedingly over patients who become Christians in the hospital, and who take an active part in the chapel service. These 20 nurses have 63been trained by the Doctor herself, and one small room off the dispensary treatment room has a bench in it where some of them gather when the Doctor has a few moments that are less crowded than the few moments that precede and follow them, and where she teaches them the necessaries of anatomy and treatment.

"One could see the patients brighten as the doctor went her rounds"

(the doctor at the left)

Her sister-in-law, the head nurse, is very efficient, and possesses, among other things, a rather peculiar charm of manner and winning power that must make her acceptable to everyone of the other 19 nurses. One can feel, not only in contact with her one's self, but in seeing her relationship with the others, that she has a temperament which seems wholly unruffled by impatience and apparently never at a loss to know what to do.

The head operating nurse, a Miss T——, is a young girl of about twenty, who is not only clever in handing instruments and foreseeing needs, but is also a most devoted helper and faithful and reliable attendant on the critical cases. Dr. Stone said that she gave her most severe 64cases to Miss T——, who seldom failed to nurse them back to health again.

Miss T——'s temperament is buoyant and also noticeably spiritual. It appears, that through no fault of her own and doubtless without any consent of her own, she was engaged to a young man before she became a Christian. When she was converted and had a new view of life she longed to have him see things as she did and for him to have the opportunities for an education which she had. When one considers that Dr. Stone receives $450 a year as salary one can imagine that the nurses of her hospital cannot receive very much, and this brave girl began saving her coppers to put them together that they might spell out for this young man a chance for an education. Perhaps few know what ambitious self-denial can do, and the young man was duly installed at the William Nast College with this continuous brave effort in the background to keep him there; but he did not learn with interest, and one surmises that he was kept in the college because the faculty knew of 65the struggle which was going on in his behalf. Intemperance had also a part in his life, I believe. At last, after some rather discouraging months, he came to her and said that the food at the college was not good and that he wanted her to give him more money so that he might have some extras which most of the other young men did not have. At this juncture some friends of Miss T—— stepped in and the engagement was broken, and, of course, we of the Occident should remember that the affair had not considered her assent in the first place.

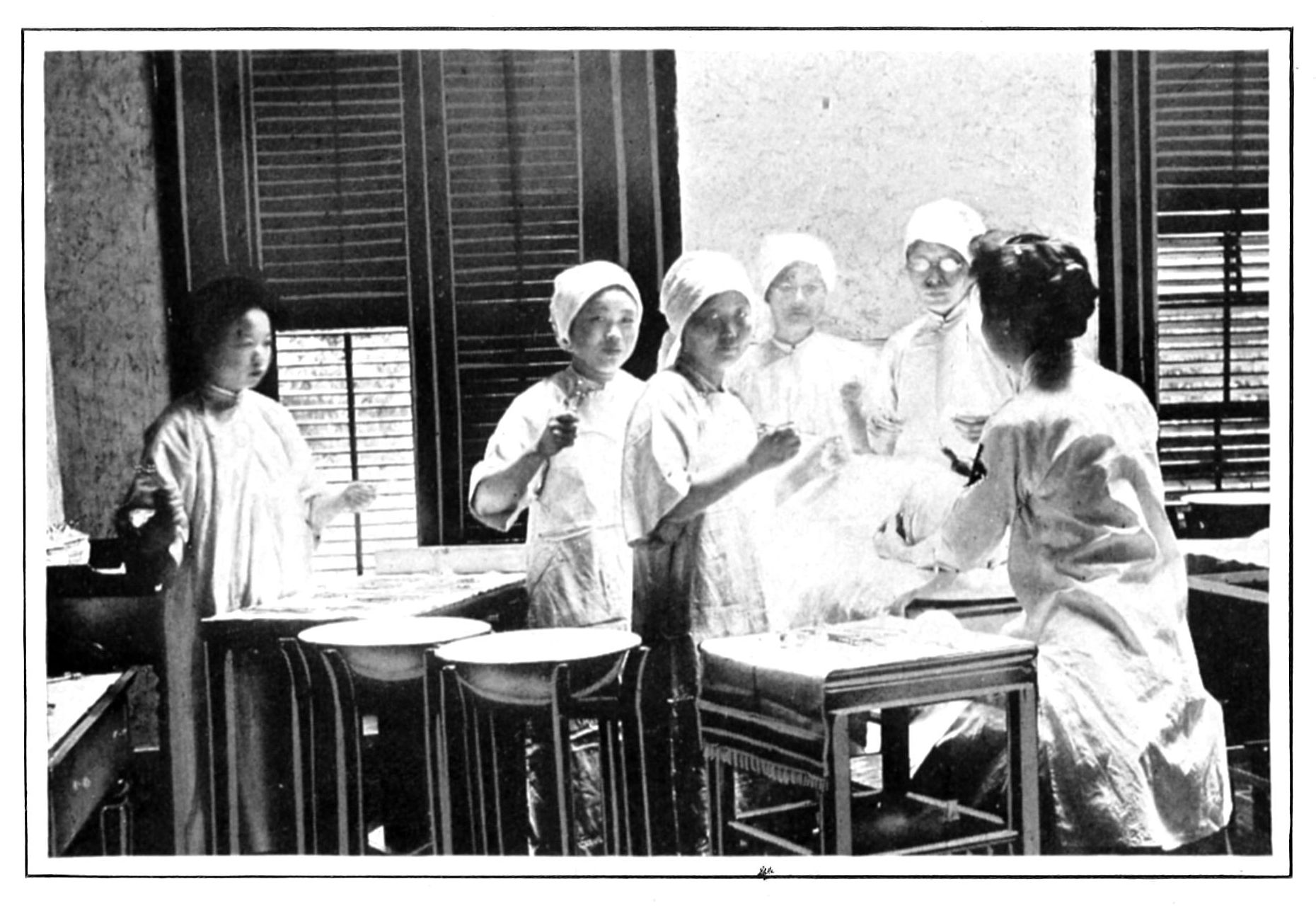

"Clever in handing instruments and foreseeing needs"

With the same devotion Miss T—— is, at present, helping two of her brothers who are in the William Nast College. The older one is an exceedingly handsome young man with hair that is not straight, as is most of the hair in China, but is somewhat wavy, and a face, which like Miss T——'s own, has a power of lighting up in a way that is almost the unmistakable mark of the Christlike life in the heart. He and his younger brother have scholarships in the College, but the rest 66must come from their sister; their books and their clothing and their spending money, which surely cannot be a large amount. One of these young men, the older one, had been troubled by a cough and weakness for some time, together with some slight hemorrhages, and, upon examination, it proved that he was rather an advanced case of pulmonary tuberculosis. Some examinations of the other young men showed that this condition was not uncommon in the College, and a following extract from one of the recent letters from the Doctor bears somewhat on the subject.

It should be remembered that while Dr. Stone does all that she can for the young men of this Christian School and College she cannot by any means do all that she wants, and her visitor during the few days of the stay there made a physical examination of quite a number of the young men and found that a good many of them needed special attention, but at the time when it was necessary to come away there were still some thirty young fellows who 67wanted to be examined and felt in need of it, and yet the time did not permit.

Perhaps it is the stress of the surrounding heathen world and the very different sentiment which pervades the neighborhood on all matters that brings a unity and harmony into the College which, if one may judge on a rather superficial acquaintance, exceeds that which one finds elsewhere. There appears to be a great deal of good feeling among the students. One scarcely needs to remark on the courtesy with which one is received, that is rather universal whether in a Christian Chinese atmosphere or no.

The girls, who live in a separate compound which adjoins that of the young men, come filing into the church used by both schools two by two, and make their exit in the same way, before the young men are allowed to go out. The monthly Epworth League meeting, which comes on a week day night and rather more resembles what we should call a "social" meeting than a religious one—although, indeed, hymns are sung—gives some little 68chance for the young men and young girls to know one another at least by sight. I attended one of these meetings and was extremely interested in hearing the young girls sing and give recitations and to hear two of the young men debate before some judges, and, in fact, all the young men and young girls were judges.

These speeches by the two contestants were greeted with laughter and applause and it sounded very much like debates in this country. The judges' decision was greeted with applause and evidently satisfied the audience. The debate was for and against "The Reality of Omens," which was decided against their value. It seemed appropriate that the young man who supported the more benighted belief should have chosen the Classical Chinese for his address; a language so unfamiliar to his audience that many of them could not understand parts of what he said and he himself had much difficulty in remembering his debate. Like the omens themselves, this style of language is becoming less and less useful as the old form of ex69aminations, on the Classics only, is a thing of the past. That particular kind of classical vocabulary is difficult even for the Chinese themselves, and the phrases are unintelligible until duly explained and carefully learned. It is true that the Classics are still taught in all schools, even the Mission Schools, and form, by right, a part of the Chinese education, but they are taking more and more a second place in the light of more useful and practical things.

On each occasion when nightfall overtook the visiting physician on the college campus, at some distance from the hospital, the Little Doctor, despite the multitude of other matters pressing, never failed to send over one of the faithful coolies from the compound with a lantern as escort along the dark streets toward the hospital. The Doctor has what is nothing short of a talent for detail, as one may judge from the fact that her activities include besides the care of the hospital, with its six hundred in patients a year and many skillfully performed operations—70even to ordering her own drugs from Shanghai—the extra burden of the dispensary with its fourteen to fifteen thousand annual calls, and in addition to conducting a home and caring for four boys—clothes, education, ailments, discipline, and all—the responsibility in good part of three schools, one, a most important school, The Knowles Bible Training School, which does supply and is to supply evangelistic workers. And, one may add to all this, a general supervision of the fine new buildings of the last-named school which are under construction, and the writing of many letters. And with all this the Little Doctor is the soul of geniality and the well merited exhortation "Quaisi, Quaisi!" (Hurry, Hurry!) to some slow-moving Chinese is said so kindly or genially that nobody has an excuse for feeling hurt.

"And many skillfully-performed operations"

It is doubtless true of most medical work that its variety lends interest and prevents monotony even to long periods of work, but something more than just the different experiences must enter into one's 71heart and life to make one ready to take, as Dr. Stone has done, years of consecutive work, without so much as a week's holiday, and no one who works with her even for a short time will fail to recognize that that source of energy is hers according to the promise: "They that wait on the Lord shall renew their strength." At the time of Dr. Stone's own illness, some five years ago, when she was confined to her bed with appendicitis, the outlook was bad should she stay in Kiukiang, for the people in their eagerness to be helped or to have their children helped, could not be kept out of her own home, and the women would come in with their little sick babies and find their way up the back stairs and into the sick room where the Doctor lay, and so, on all accounts, it was necessary that there should be the operation and convalescence somewhere where the burden of the work would be taken off her heart.

So the trip to America with its time of sickness and recovery had also some small periods of rest before the Doctor resumed her work in China again. And now, the 72work goes on with still more demands than before.

One rather strenuous day stands out especially in my mind. We had operated most of the morning, with dispensary work thrown in, and operated for a long time in the afternoon again.

The afternoon case was unusually critical, and the patient, a little baby in a dying condition already, nearly succumbed on the table, but was put in a little basket like a cradle whose foot was raised in order to sink the head and there it lay recuperating. The head operating nurse and most competent caretaker was given charge of the case, and it may be stated here that, according to latest reports, the child, who has been named Strong Grace, is still alive. The father of the child tried to show his appreciation for my share in the operation by giving me the next day a cold boiled sweet potato, and the mother found expression to her feelings a couple of days later by entering the operating room where we were preparing for an operation and going down on her knees on the floor 73before the visiting physician, much to his embarrassment, be it said, since explanations were hopeless. The situation was relieved by the Little Doctor, who explained to the woman that we never get on our knees to people, but only to God.

We went back to the house to dinner and had laid down the responsibility of the day's work, and entered with our hostess into her atmosphere of most delightful sociability. One would think when the day's work is over that there never had been anything of responsibility to weigh on her powers of solving problems. Dinner was hardly more than well begun before a messenger came to say that there were some cases of very severe sickness that had just arrived at the hospital. We hurried across the lawn and through the corridor, and I can not forget the sight of the reception hall where these sick people and their friends were gathered in a rather confused group, those who were suffering being too ill to stand. It appeared that there were six cases of ptomaine poisoning. A river steamer, on its 74way up the Yang Tze, had stopped at Wu Hu, where some of the native passengers had bought some shell fish which they had eaten and which had caused serious illness shortly afterwards. One of them died before the steamer reached Kiukiang, and the rest were brought in chairs to the hospital door for help. Two had already been carried up stairs and laid upon beds, and the remaining four were helped up to private rooms, the Doctor remarking to me, with a touch of amusement, that whereas her hospital had been for women and children, it was turning into a "general hospital," two of the patients being men. We worked for some time on behalf of the newcomers, and though one more case developed the next morning all seven recovered. Four of them were native preachers and their wives returning from Conference at Nanking on their way to the Nan Ch'ang District.

When we could return to finish dinner, it was quite late and when the time to retire came it was not to be for a long rest 75 for the Doctor, for the youngest of her little charges, Wesley Mei, had rather a bad attack of coughing in the early morning, starting about 3 o'clock, and the Doctor was up with him and did not get to sleep again, and so began the next strenuous day with its many appeals and many suffering dispensary patients and its many decisions to make.

Apropos of decisions, one of the most remarkable traits of Dr. Stone is her ability to make decisions rapidly and the ability not to question them when made. It seemed to me for some time that the secret of finishing so much work in a day was due rather to this one fact of making these decisions and then not reviewing them afterwards, leaving them behind and unchanged just by will power, but a little longer familiarity with her mode of thought suggested, I think, a truer solution, namely, that her thought is so entirely unselfish and guided by a higher wisdom that the decisions which are made are made correctly and not arbitrarily disposed of. The same American woman of wide 76experience referred to above has said of the Little Doctor that she is the most "selfless" woman she ever knew; and that, of course, is quite without a thought of a lack of personality, for that is most marked, but rather that she has the secret of unselfishness which is always to be thinking of somebody else.

When the preachers and their wives of the Nan Ch'ang District were quite well again we were invited with them to a Chinese feast served in true Chinese style in the room that is fitted with the native decorations in the home. It appears that the place of honor at a Chinese table, which is set without a cloth, is at such a point that the grain of the wood does not run toward one. This is a fine point which we should not have noticed had not our attention been called to it. The feast was served in bowls at the centre of the table, and all ate with chop sticks, the honored guest being the first to help herself from the central bowl. The Magistrate's wife, mentioned more in detail later, was one of the party, and this was indeed a con77cession on her part to the Christian notion of fellowship, for, in China, in the true Chinese style, to have gentlemen and ladies dine together is perfectly impossible. Two of this party at table found some difficulty in wielding chop sticks and were helped with a good deal of courtesy and without undue merriment by their Chinese neighbors at table. Another of the guests was the District Superintendent of the Nan Ch'ang District, who also was on his way back to his charge from the Nanking Conference.

The social gifts of our hostess were indeed put to the test at this function, and it is still rather incomprehensible to me how the Doctor could act as interpreter for two sets of conversations, that between my mother and her neighbor and between myself and my neighbors, and yet keep on talking most affably with all the party, and when the meal was over it was not with a sensation on our part, that there had been much of a barrier of language between us and our friends. The same facility of acting as a medium of com78munication was constantly observable, or rather almost unobservable, and both in speaking in public and in the hospital work the matter of the difference of language shrunk to a very small factor, indeed.

One opportunity to speak to a Chinese audience was at the Rulison High School where the bright and interested looking young girls gather each morning for their chapel service. Among these is a child who was stabbed by her mother-in-law and thrown out to die. Before going out to China this incident had been reported here in this country, and I expected to see at least a girl of 15 or 16, and was surprised when a mere child responded to Dr. Stone's request that she should stay after the rest went out. Another child who stayed had been the slave of a woman in Kiukiang, and had been so terribly beaten by her mistress that her back was all lacerated. In perfect despair the child ran away, not knowing where to go, frightened at everything and afraid of everybody. Dr Stone was starting out in her 79chair on some call when she saw the child at one of the angles of the street crying bitterly. She stopped her chair and got out to investigate. The bystanders hadn't much to tell, but Dr. Stone managed to get at some of the facts, saw that the child was in need of medical care and invited her to go back to the hospital with her. The frightened little girl refused, having no confidence in anyone, but the bystanders told her to go along with Shü-Ee-Sen, that she would then be well off. So the child went back to the hospital, and subsequently, upon being healed, went to the Rulison High School, her mistress being more willing to forego the possession of her slave than show her identity by claiming her again. This is by no means a unique instance.

One day a man brought a little girl to the hospital who was in a very neglected condition, among other things her hand was infected with tuberculosis so that one or two of the bones had to be removed. Dr. Stone asked the man whether the little girl was his slave, to which he replied 80that she was not. Not long afterward, and while the child was still in the hospital, a native woman came and visited the wards and, with boundless joy, recognized and claimed in the child her own little girl. It appeared that the father was a slave of the opium habit, and that one day, while the mother was working, he had taken his own little girl, and hers, and sold her into slavery to get money for more opium. It was true that the child did not belong to the man who brought her, but was the slave of his brother; but the child was restored to her mother again.

When one thinks of the unfavorable status of even the wives in the family there one can form some dim conception of what slavery must be like; and not alone have the victims of this system no possessions, but they have not even the possession of a name; and it is "Slave girl, come here!" "Slave girl, do this!" Only a year and a half ago some 200 women and girls were sold on the streets of Kiukiang as slaves to whoever chose to come and buy. One reads in the chapter in the 81"Bonnie Briar Bush" that is entitled, "His Mother's Sermon," how the Dominie, walking in the garden, treads under foot a rose, and one tries to fancy what his state of mind must have been to make him do a thing like that; but can one get a vision of what darkness of heart it must be that can take a human life, with all its beauty of possibility, and crush it?

The light of the Gospel brings quite a different feeling toward womanhood, and one of the little children in the Primary Department of the School connected with the Rulison High School has an interesting story, even though her life has extended over but a few years thus far. A letter carrier, who was a Christian, found a little baby girl in the road who had been abandoned to die. It did not seem to his awakened conscience at all the right thing, so he picked up the little bundle and cast about in his mind what might be done. From his slender resources he could not save enough to hire a woman to take care of the child, so when he came by boat to Kiukiang he consulted with a clerk in the 82post office there who also was a Christian, and they decided that they would unite in saving sufficient to pay for the little girl's care. The Little Doctor heard of the child and took her under her own protection, placing her as soon as she was old enough in this school, and now the child is supported by a lady in this country and has the name of Abbie Knowles. One cannot help being glad when looking at that exceptionally sweet-faced girl with her dark eyes that Abbie Knowles should have been found by someone whose heart the Lord had touched.

One of the patients at the hospital was a little boy suffering from pulmonary tuberculosis. He was the son of a man of some rank in Kiukiang, and both his mother, one of the guests of the Chinese feast, and his nurse lived in the hospital in order to watch over him. It was really touching to see the solicitude of both of them. His little sister, too, was one of the hospital inmates, although not in the least ill, and such a bright little mite of humanity as she was, scarcely over a year 83old, but noticing strangers, and, quite to our surprise, attracted by the looks of foreigners, and a number of times I have looked down to see this little child in the attitude of a Chinese woman's salutation, waiting to be noticed. The little boy had three white rabbits with him that lived in a box in his room and ate uncooked rice, or accompanied him to a lawn where he was wheeled up and down in a little rolling chair by his nurse. His father seemed to be a most pleasant and most responsive man.

News has come from Kiukiang that the child went back to his home improved, but more important than that was the fact that his mother, not only experienced the breaking down of Chinese prejudices but entered into the further experience, the consummation of all life in a true conversion; and when one considers the position which she held and the separation which the official class feel exists between them and others it is nothing short of a miracle that she should have thrown away her idols and her ancestral tablets, too, the 84greatest treasures of which a household can boast, and said to the Doctor, "I have just fallen in love with your Jesus."

Many conversions have resulted from the faithful work and the prayers of that devoted band of Christians. One woman who went home a Christian from a long stay in attendance upon her little son in the hospital returned later bringing her son, and together they went through the hall and up the stairs into the ward and to the very bed upon which he had lain sick so long, and there they knelt together to thank God for his recovery.

"That devoted band of Christians"

The ten days at Kiukiang seemed both long and short; long because of the variety of experiences and short because of all the interest and the pleasure of the visit.